Pages

1.25.2021

1.23.2021

The Sunday of Deceased Priests

The Three Weeks of Commemoration

On this Sunday we commemorate our Deceased Priests. We celebrate this liturgy, and continue our remembrance during the following week. After that, we remember the Righteous and the Just, and then all the Faithful Departed. These three weeks comprise a sort of transition from the Season of the Epiphany, to Lent. They are indeed a preparation for the great season of mortification. There are no obligations of fast and abstinence during these three weeks, other than to abstain from flesh meat on Fridays.![]()

The best way to think of these three weeks is to compare them with 1 and 2 November (All Saints and All Souls Days) in the Latin Catholic Church. They have two days, we have three weeks – an echo of the Maronite emphasis on remembering the deceased. The second week of the Maronite commemorations corresponds to the first of the two Latin feasts, All Saints Day. Then, our third week is the equivalent number of the second feast, All Souls. So, why do we have a first week? We do so because this is the theology of the Maronite Church: that the entire calendar begins with the Consecration and the Renewal of the Church. In its wisdom, the Maronite Church paints the background to the liturgical year and to the period of commemoration.

We begin our year with recalling that the Church is the medium through which the Word of God and His healing sacraments have come to us. And we begin this mini-Season by praying for the departed priests, because if they had not passed on the faith and the sacraments, we would not have the faith.

The Commemoration of Deceased Priests

To anticipate, this feast is not only about remembering deceased priests, it is just as much a reminder that the Christian priesthood is a participation in the eternal priesthood of Our Jesus Christ, the High Priest. The work of priests is for our eternal salvation, and although we only see the body of their hieratic work in this world, its roots and its highest fruit are in the Kingdom of Heaven. Our Christian life today is for our Christian life in eternity.

Of this icon, Fr Badwi wrote: “Our fathers, the priests, who preceded us to eternity continue their celebration there and preach the Bible upon the altar of the luminous world, surrounded by worshipping angels. All this happens in an eschatological scene, presenting the All-Powerful with the two eternal suppliants, the Virgin Mary and St John the Forerunner, surrounded by a crowd of saints and angels who carry trumpets and scales.” Let us unpack this.

First of all, we are shown in heaven, and even in that divine world there are levels. Enthroned in glory at the top, is the Lord. To His right is His blessed mother, and to His left, St John the Baptist, His cousin and forerunner. They are interceding for humanity. This is an important detail, because it links their action to the prayers of the faithful at each and every divine liturgy, and in the sacraments. Think of this icon when you next approach the sacrament of confession, and you will make the connection – just as you present your sins to the Lord through the priest, so too in the court of heaven you have powerful advocates joining their prayers to yours.

Next, in the lower level, but still in heaven, there is what Fr Badwi calls a “luminous altar,” perhaps because it is the colour of the evening sky. Standing upright at it, are two deceased priests who have been admitted into heaven (note the haloes around their heads) celebrating the divine liturgy. We know that the liturgy is celebrated in heaven because of the revelation to St John the Divine (see chapter 4 of the Apocalypse). They are concelebrating the service. One has the Gospel before him for the Liturgy of the Word, while the other – who is a bishop as his staff shows – has the chalice and paten for the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The bishop may also be a monk, but since all Maronite bishops wear the monastic cowl, one cannot be sure. This bishop and priest stand for all bishops and priests.

The angels who are bending in reverence towards the altar hold the staves of messengers (the word mal’ak or “angel” once denoted “messenger”, being literally “the one who goes.”) They represent the fact that the Divine liturgy is celebrated as a result of and for the Word of God, and that angels are present whenever it is celebrated – even on earth. The default Maronite communion hymn reads: “The hosts of angels have come to stand with us at the holy altar …”

Fr Badwi says that the icon presents an “eschatological scene.” Eschatology is the study of the final days, the end of the world, the judgment, and the eternal life. The angels with the trumpets and scales are angels from the Book of the Apocalypse, heralding the last days with trumpets: they have scales in Revelation 6:5. These old-fashioned scales or balances are unknown today, on one side would be a placed a specific weight, e.g. two ounces, and on the other side, an object (often a precious object such as gold or silver). If the gold weighed less than two ounces, the weight would sink lower than the gold. When the two sides of the scales were balanced, then by measuring the weight, you knew how heavy the gold was. The gold in this case is our souls, and the weight is truth.

The priest is a mediator, a bridge, a channel, a conduit. But, and this is often forgotten, he is specifically a mediator, a bridge, a channel, a conduit for Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and not for some vague heavenly power. From that perspective, the priest is also a representative. This leads to my final point: the upper portion of the picture, at the throne of God, is reflected in the second half: Jesus is present on His throne, Jesus is present under the sacred oblations on His altar; Our Lady and St John intercede for us in heaven, and the bishop and priest do the same at the altar. This is one of the central truths of our faith – and a comforting and consoling one, if we could but meditate upon it.

Note: Sometimes people ask whether these three weeks belong to the Season of the Epiphany. They do not, and cannot: we do not use the Epiphany response to the Qadishat (we say “itra7am 3alayn” rather than “mshee7o det3amed men you7anon, itra7am 3alayn”), and wear different liturgical colours.

1.16.2021

Saint Anthony of the Desert - January 17

Anthony the Great is believed to have lived for 105 years, from 251 to 356, dying on 17 January, the day when we celebrate his feast. He was born in ancient Egypt, while the pagan religion was shrinking but still alive there, although by the time of his death it, too, was about to expire. His parents were Christian, and wealthy. He was a religious and contemplative child. At the age of 18 he was orphaned, and so probably became wealthy. But at church he heard a voice saying: ““If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow Me.” (Matthew 19:21) He did just that, donating all he had to the poor, and pacing his sole sister with some good women.

Although he had a teacher in the solitary life, he went to live in a graveyard outside the village (which is where all graveyards were at that time). He survived on bread and water, and often stayed inside a tomb, so that he could remain alone. He was plagued with temptations by the Evil One, who would appear to him, sometimes in human form, sometimes in bestial form, or as a monster. According to St Athanasius, whose biography, written only a few years after his death, is our best source for him, St Anthony realised that the form the devil took was related to his own interior state. That is, the devil was tempting him where he was weakest.

It is said that in about 285, when he was almost 35 years old, he was so affected by the crowds of people who came to see him, that he went to live in an old fort or castle on the Nile River. There he remained for twenty years, living as a hermit, until he had obtained mastery of his thoughts, desires, and emotions. There is a very great truth here: a person who can force themselves to live alone can in fact build up a tremendous power inside, because they have to overcome the desire to be with others and to see the rest of the world, endless times each day. However, he did have pupils: people who were attracted by his reputation for holiness and impressed by his austerity took up residence near but not with him. Again, this is true: a person comes to a certain stage of spiritual development and then they must teach others if they are to progress, after all, there are things one can see in others but not, at first in oneself. But once we have seen them outside, we can see them inside.

In 311, he learnt that the Christians were being persecuted in Alexandria, and he decided to go there himself and to encourage them to stand fast. He would have been 60 years of age. This persecution, part of the Diocletian, was so vehement that it is said 660 Christians were killed there in the eight years up to 311. The fact that the persecution in Alexandria went on for that length of time before St Anthony went to their help tells us that the sort of communication he had with others was probably entirely spiritual. He was such a commanding figure that, in Alexandria, he was not himself attacked.

When this was over, he retired to a spot on the Red Sea, called Mount Colzim, where he had a cave, water, and some palm trees. He grew wheat, and if people brought him anything, he gave them one of the baskets he was weaving to keep himself usefully occupied. Here he obtained great fame as the organizer of spiritual life and solitary discipline: even if the solitaries lived near each other in order to render mutual support. At about the age of 85, in 335, he went to Alexandria at the request of St Athanasius to preach against the Arian heresy. However, he returned to his cell, for, he said, a monk out of his cell is like a fish out of water. As he grew older, he needed to be cared for, and two monks helped him. He ordered that his place of burial be kept secret so that there be no cult over him.

While his place of rest has never been found, he has been the centre of devotion for his extraordinary victories in the spiritual life, and the teaching and example he gave to others. He is greatly honoured among Maronite monks for his contribution to monasticism, and hence is honoured by all Maronites.

At the monastery of St Anthony, Qozhaya, named after him, they have this extraordinary painting . In one picture, we see the whole of the spiritual life and how to live it. First, we see the saint himself. He is looking down in humility, but he is not stooped – he is upright in Christ, and unembarrassed. He is elderly, and walks with the aid of the “tau” walking stick – the “tau” or capital T was how they depicted the Cross on which Our Lord was crucified.

The picture is read from our left to the right: to our left (his right) is the cave in which he lived and from which the beast has come. This represents the sinful impulses inside us. But he leant on the power of God, represented by the tau waking stick, and so the creature is tamed and lies quietly at his feet. The bell on the staff is used to call the beast to be quiet (it is sometimes said to be a pig, but here it is clearly a monster). This is very profound: our memory of our sins never disappears, but the sinful impulse is tamed, and if it rises up, a little ring on the bell, and it takes its proper place.

Both the sun and the moon are in the sky and shining because he is no longer in earthly time when it can only be day or night. He is beyond life and death, he is in eternity. The final detail to remark on is the book. He may have been illiterate, which means that God’s universe and the laws He writes on our hearts were St Anthony’s book. He has the book but he does not need it: he reads without looking at a word, because he reads with the eyes of faith.

May his prayers always be with us.

1.09.2021

The Epiphany

Feast of the Epiphany falls on 6 January, and inaugurates a Season which runs until the three weeks of commemoration of the departed, the immediate prelude to Lent.

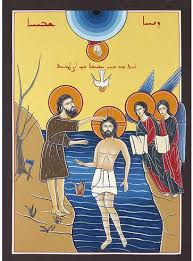

The icon gives this feast its proper Syriac name, the denHo. This means “the rising of the sun or stars, sunrise, dayspring; brightness, light.” Metaphorically, it refers to “the shining forth or manifestation of the Lord in the flesh.” The 3eedo d.denHo is the Epiphany, the Greek word for “manifestation.” Therefore, the Syriac term for this feast and its season is a more comprehensive word than the Greek. The fact of the matter is that no one really understands what the English means: there is even uncertainty is the Latin Church whether it refers to the worship of the Magi or the Miracle at the Wedding at Cana, too.

But to see this feast as the “Rising of the Sun” is to illustrate in one simple phrase what it should emotionally mean to us. To think of it as the “Rising of the Star” is also appropriate, and should lead Christians to reflect on the prophecy that “there shall come a Star out of Jacob, and a Sceptre shall rise out of Israel …” Numbers 24:17. It also reminds us of the Star of Bethlehem, and indeed, in typology, all these stars are manifestations of the one star. In other words, in Syriac thought, the feast of the Epiphany reminds us that the Lord Jesus is the source of all light, and especially of spiritual light; He is the true sun, the true star; and when we see these in the heavens, we do well to lift our hearts to Him, too.

To recap, this feast is called the “epiphany,” “manifestation,” and “sunrise” because it is when Our Lord, who had been living quietly in his Nazareth home appeared before all the world. To us, we also see it as the first public manifestation of the Trinity.

When he prepared this icon, Fr Badwi had before him four ancient examples. Three of them are very close indeed to this icon. When we contemplated the icon of the Annunciation to Our Lady, we saw that the water in the well was drawn as if it was standing up all by itself. These three icons had something exactly the same with the river: it stands up from the ground like a pyramid, so that the head of the Lord is barely lower than that of St John the Baptist. Of this icon, Fr Badwi writes:

The Trinitarian element is represented: the Father by the chirophany (the appearance of His hand), which is a symbol not only of the Creator but also of His voice. He is seen by His incarnate Son, baptized in the Jordan by the Forerunner. The Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove, descends from the heights and rests on the head of the Son. The angels hasten to carry towels to dry the Ember who has been baptized, symbolized by the flame coming out of the water. This is unique to the Syro-Maronite tradition. The fire and the water are the image of the divinity united to the humanity through the person of the incarnate Son of God in the perfection of His two natures.

This feature of the divine nature as fire is shown very clearly in the Rabboula manuscript, where along the right hand side of the picture, we see the Father’s hand pointing down, directly beneath it is the dove of the Holy Spirit, and directly beneath that is the pillar of fire which is ascending from the River Jordan where the Lord is being baptised. Here, Father Badwi has done something a little differently. He has drawn the seven fold sphere of heaven in the top middle of the icon, giving it the most important position, showing that all which unfolds beneath is being directed by God. To the right and left of the seven heavens are written the words “the Glorious DenHo.”

The Father’s hand is slightly but unmistakably titled towards the right of the viewer because the Lord Jesus is seated on His right. Beneath the hand of God are the words “This is my beloved Son.” This shows that the hand of God also represents his Word – both are ways of understanding the creative power of God (which is One in itself, as all in God shares in His Oneness). The Holy Spirit has descended, and now overs the head of the Son. The fire to which we were referring seems to float above the water, almost as if it were a flower on the surface of the river. This also ties in with the Maronite theme that when Our Lord was baptised, spiritual fire filled the water, and all the waters in the world were purified.

The axe by the tree which is behind St John the Baptist is also important: he said that when Pharisees and Sadducees came to the River Jordan to be baptised, St John said to them: “Produce good fruit as evidence of your repentance … every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire” (3:8 and 10).So when we read this icon from left to right, we begin with the need for repentance for our sins, and the warning that the tree of evil is about to chopped down. Then we come to St John the Baptist, who is wearing rough clothing to signify his own poverty and mortification of the body, and then, in the middle, Our Lord, being baptised. To the right are the angels who are there to tend to Him. The presence of the angels reminds us of the words of St Matthew, who immediately after the baptism of the Lord, as His temptation in the desert, which ends with these words: “… and behold, angels came and ministered to him” (Matthew 4:11).

Of course, the angels also represent heaven, and therefore salvation. So reading the icon from left to right, we have this sequence: penance, the Lord and His sacraments, the angels of heaven. Not every icon can be read this way, but when the icon tells a story, it often will be that way.

1.04.2021

The Nativity of the Lord

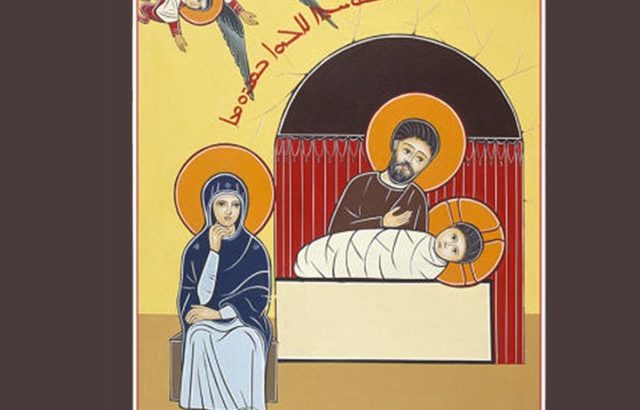

Christmas Icon was produced after the manner of the Rabboula manuscripts. Fr Badwi writes: “The Blessed Virgin is seated with her hand on her chin, thinking and meditating on this great event, the miraculous birth which initiates the history of salvation. She is modelled on the Muse of History in Greek mythology. Near her lies the wrapped child, in the form of an altar and tomb. He is born to be sacrificed and to die for us. Joseph the Just is respectfully inclining behind the manger. The grotto and the veil stand for the grotto in Bethlehem, despite their unrealistic form. Angels trans-pierce the celestial circle, singing “Glory to God in the Highest,” written her in Syriac.”

Christmas Icon was produced after the manner of the Rabboula manuscripts. Fr Badwi writes: “The Blessed Virgin is seated with her hand on her chin, thinking and meditating on this great event, the miraculous birth which initiates the history of salvation. She is modelled on the Muse of History in Greek mythology. Near her lies the wrapped child, in the form of an altar and tomb. He is born to be sacrificed and to die for us. Joseph the Just is respectfully inclining behind the manger. The grotto and the veil stand for the grotto in Bethlehem, despite their unrealistic form. Angels trans-pierce the celestial circle, singing “Glory to God in the Highest,” written her in Syriac.”

In Liturgical Year Iconography, he reproduces some ancient illustrations he used in preparing this icon. Fr Badwi has very carefully managed to include all the important details, in so neat and orderly a form that we do not notice how much has been packed in. Compare this icon to the other Nativity Icons that come up on a web search, and you will see how uncluttered and clean it is.

First, centre stage is held by the Christ Child in swaddling bands. Today infants are wrapped in bunny rugs, but in the old days they were “swaddled,” or kept tight and warm by using strips of material. It was known in those days that the best way to keep warm is not have thicker coverings, but to use more coverings, because these trap the air between them, and that warm air is the best protection of all. Notice how the Christ Child lies on the cradle: it is presented as if it were an altar, and he the Holy Offering upon it.

An altar is integrally related to a tomb, because it is a place of sacrifice; where life on one level is exchanged for life on a higher. But because it is that type of tomb, the altar is a tomb which points both to resurrection and to death. The altar is a tomb where death is not just reversed into life, but is raised into a higher life.

The next figure after the Lord, is surely St Joseph, who is bending towards his foster son in a simple and dignified gesture of piety. He is both gesturing to the child and also to his own breast, as if he is saying: “This child is in my heart.” The Lord’s eyes are looking directly at us, but St Joseph’s and Our Lady’s eyes are gazing across our right hand side of the icon. The angels are looking down, diagonally, and across, but not at us. We are engaged, in this icon, by the Christ Child and by Him alone. He is absolutely the centre, and His halo is already marked with the sign of the Cross, while those of the other holy figures are plain.

Note that behind the Lord and His foster father, there are cracks coming from the top of the arch. Remember that these represent the grotto in Bethlehem. The veil, which Fr Abdo refers to, is also the veil of the Temple which will be split when the Lord dies on Good Friday (Matthew 27:51; Mark 15:38; and Luke 23:54). Hence, I suggest, the cracks, because from the moment of the birth of the Lord, the old order is being prepared to pass away, having fulfilled its divine purpose, and being fated to be surpassed and superseded by the New.

When Fr Badwi writes that Our Lady was modelled on Clio, the Greek Muse of History, he must mean in the calmness of her expression. I have looked at a number of illustrations of her from ancient Greek art, and in none of them is she shown in this pose. Usually, she is shown with a trumpet, or with her right hand raised, and a finger pointing upwards, for she is known as “the Proclaimer,” since history makes great events known. Yet, Clio herself is not shown as excited or emotional. The one who reads history must read carefully and attentively, not being swept away by their feelings. This does fit in with the image of Our Lady as being the one who pondered all these things in her heart (Luke 2:19 and 51, although to be fair to St Joseph, St Matthew tells us that he too pondered what he had seen: Matthew 1:20).

And this brings us to the very greatest difference between this depiction of the Nativity and any known to me from the Western tradition. There are very few, practically no, representations of St Joseph tending to the child at the crib, while his mother is sitting before him. There are of course many depictions of St Joseph holding or nursing the infant, but almost never with Our Lady present, but watching rather than participating in the scene.

Yet, this feature is shown in the ancient example from the Rabboula manuscript which Fr Badwi gives as an example of the illustrations he used in preparing his icon. So, even in the Syriac tradition, there was a tradition of depicting St Joseph tending for the Infant Jesus as he lay in his swaddling bands, as Mary sits apart meditating. Why?

I suggest that here Our Lady is the middle, between the angels who appear from out of heaven on high and her husband. She does not know all that the angels know, but she does realise that she is present before a very great mystery, and so she seeks understanding. Our Lady’s posture is a reminder not to allow ourselves to become lost, even in the adoration of the Lord. We are not made to lose ourselves in worship, but to find ourselves in contemplation of the divine.

Finally, one another strange feature is found both in this icon and in the Rabboula original, but never in Western art: the Infant Jesus is depicted at approximately two thirds the size of the adults. He is still a child, but he is more. I think the reason is that he is already complete in his divinity, although as a human he still has to grow. There was a feature in ancient art where the most important figures (e.g. a king) were always depicted as larger than the others. This depiction of the child as extraordinary in size is done with the same feeling: but he is not shown as larger than the adults, only as preternaturally big for a baby.

So there are two rather unusual aspects in this aspect which only come to light when we meditate on it: the reversed positions of St Joseph and Our Lady from what we would expect, and the disproportionately large depiction of the Lord. These things have a feeling impact on us, even if we cannot always explain why. They make an impression.