by

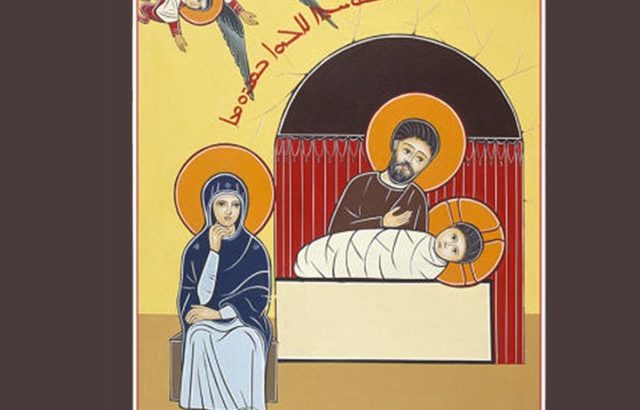

Christmas Icon was produced after the manner of the Rabboula manuscripts. Fr Badwi writes: “The Blessed Virgin is seated with her hand on her chin, thinking and meditating on this great event, the miraculous birth which initiates the history of salvation. She is modelled on the Muse of History in Greek mythology. Near her lies the wrapped child, in the form of an altar and tomb. He is born to be sacrificed and to die for us. Joseph the Just is respectfully inclining behind the manger. The grotto and the veil stand for the grotto in Bethlehem, despite their unrealistic form. Angels trans-pierce the celestial circle, singing “Glory to God in the Highest,” written her in Syriac.”

Christmas Icon was produced after the manner of the Rabboula manuscripts. Fr Badwi writes: “The Blessed Virgin is seated with her hand on her chin, thinking and meditating on this great event, the miraculous birth which initiates the history of salvation. She is modelled on the Muse of History in Greek mythology. Near her lies the wrapped child, in the form of an altar and tomb. He is born to be sacrificed and to die for us. Joseph the Just is respectfully inclining behind the manger. The grotto and the veil stand for the grotto in Bethlehem, despite their unrealistic form. Angels trans-pierce the celestial circle, singing “Glory to God in the Highest,” written her in Syriac.”

In Liturgical Year Iconography, he reproduces some ancient illustrations he used in preparing this icon. Fr Badwi has very carefully managed to include all the important details, in so neat and orderly a form that we do not notice how much has been packed in. Compare this icon to the other Nativity Icons that come up on a web search, and you will see how uncluttered and clean it is.

First, centre stage is held by the Christ Child in swaddling bands. Today infants are wrapped in bunny rugs, but in the old days they were “swaddled,” or kept tight and warm by using strips of material. It was known in those days that the best way to keep warm is not have thicker coverings, but to use more coverings, because these trap the air between them, and that warm air is the best protection of all. Notice how the Christ Child lies on the cradle: it is presented as if it were an altar, and he the Holy Offering upon it.

An altar is integrally related to a tomb, because it is a place of sacrifice; where life on one level is exchanged for life on a higher. But because it is that type of tomb, the altar is a tomb which points both to resurrection and to death. The altar is a tomb where death is not just reversed into life, but is raised into a higher life.

The next figure after the Lord, is surely St Joseph, who is bending towards his foster son in a simple and dignified gesture of piety. He is both gesturing to the child and also to his own breast, as if he is saying: “This child is in my heart.” The Lord’s eyes are looking directly at us, but St Joseph’s and Our Lady’s eyes are gazing across our right hand side of the icon. The angels are looking down, diagonally, and across, but not at us. We are engaged, in this icon, by the Christ Child and by Him alone. He is absolutely the centre, and His halo is already marked with the sign of the Cross, while those of the other holy figures are plain.

Note that behind the Lord and His foster father, there are cracks coming from the top of the arch. Remember that these represent the grotto in Bethlehem. The veil, which Fr Abdo refers to, is also the veil of the Temple which will be split when the Lord dies on Good Friday (Matthew 27:51; Mark 15:38; and Luke 23:54). Hence, I suggest, the cracks, because from the moment of the birth of the Lord, the old order is being prepared to pass away, having fulfilled its divine purpose, and being fated to be surpassed and superseded by the New.

When Fr Badwi writes that Our Lady was modelled on Clio, the Greek Muse of History, he must mean in the calmness of her expression. I have looked at a number of illustrations of her from ancient Greek art, and in none of them is she shown in this pose. Usually, she is shown with a trumpet, or with her right hand raised, and a finger pointing upwards, for she is known as “the Proclaimer,” since history makes great events known. Yet, Clio herself is not shown as excited or emotional. The one who reads history must read carefully and attentively, not being swept away by their feelings. This does fit in with the image of Our Lady as being the one who pondered all these things in her heart (Luke 2:19 and 51, although to be fair to St Joseph, St Matthew tells us that he too pondered what he had seen: Matthew 1:20).

And this brings us to the very greatest difference between this depiction of the Nativity and any known to me from the Western tradition. There are very few, practically no, representations of St Joseph tending to the child at the crib, while his mother is sitting before him. There are of course many depictions of St Joseph holding or nursing the infant, but almost never with Our Lady present, but watching rather than participating in the scene.

Yet, this feature is shown in the ancient example from the Rabboula manuscript which Fr Badwi gives as an example of the illustrations he used in preparing his icon. So, even in the Syriac tradition, there was a tradition of depicting St Joseph tending for the Infant Jesus as he lay in his swaddling bands, as Mary sits apart meditating. Why?

I suggest that here Our Lady is the middle, between the angels who appear from out of heaven on high and her husband. She does not know all that the angels know, but she does realise that she is present before a very great mystery, and so she seeks understanding. Our Lady’s posture is a reminder not to allow ourselves to become lost, even in the adoration of the Lord. We are not made to lose ourselves in worship, but to find ourselves in contemplation of the divine.

Finally, one another strange feature is found both in this icon and in the Rabboula original, but never in Western art: the Infant Jesus is depicted at approximately two thirds the size of the adults. He is still a child, but he is more. I think the reason is that he is already complete in his divinity, although as a human he still has to grow. There was a feature in ancient art where the most important figures (e.g. a king) were always depicted as larger than the others. This depiction of the child as extraordinary in size is done with the same feeling: but he is not shown as larger than the adults, only as preternaturally big for a baby.

So there are two rather unusual aspects in this aspect which only come to light when we meditate on it: the reversed positions of St Joseph and Our Lady from what we would expect, and the disproportionately large depiction of the Lord. These things have a feeling impact on us, even if we cannot always explain why. They make an impression.